Professor David Kerr | Professor of Cancer Medicine, University of Oxford, Honorary Consultant Medical Oncologist, Oxford Cancer Centre

Fifteen years ago I submitted the Kerr report to the Scottish Government, with the support of civil society and all political parties, providing a framework upon which Scotland’s NHS would plan for the future.

The dominant issues of the day, which still resonate, were as follows:

Maintaining high quality services as locally as possible

Improving waiting times and access to treatment

Supporting Scotland’s remote and rural communities

Engaging clinical staff to meet the challenge of reforming the Health Service

Embracing new technology to improve the standard of care

Reducing the health gap between rich and poor

Ensuring that we get value for money across the NHS

I believed then that a truly Scottish model of healthcare would be to take a collective approach in which we generated strength from integration and transformation through unity of purpose. The people of Scotland sent me a strong message that certainty carries great weight – a commitment to ensure the timeliness and quality of care, fairly, for one and all. We made a series of practical recommendations all of which were accepted by the Scottish parliament, but which were perhaps somewhat lost in the politics of subsequent governmental change.

Never has the world been more interconnected, geopolitically, by air travel, in cyberspace, genetically and through generation of knowledge by transnational cooperation. Our NHS is under extraordinary pressure at the moment, facing an unprecedented challenge posed by COVID 19, a challenge which crosses all borders and binds all nationalities together. For me, if we are to meet these challenges, it requires us to embrace the “three Cs” of my original report: cohesion, collaboration and cooperation.

How far have we come?

If recent data are to be believed, not far enough. The envisaged Networks in which we hoped to see a greater degree of site specialisation and a better access to complex care have not come fully to fruition. I felt at the time that Scotland had done some great work in terms of delivering integrated care through telemedicine to more remote communities and would have hoped that more progress would have been made with a greater degree of governmental support.

Of course, many improvements have happened since I made my report. Importantly, we see that there have been improvements in outcome from the major chronic diseases, a tribute to my healthcare colleagues and their multi-disciplinarity of approach.

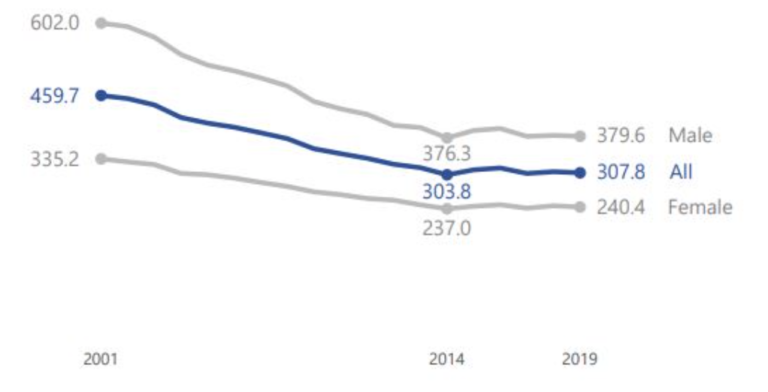

Avoidable mortality rates per 100,000 by sex: 2001-2019

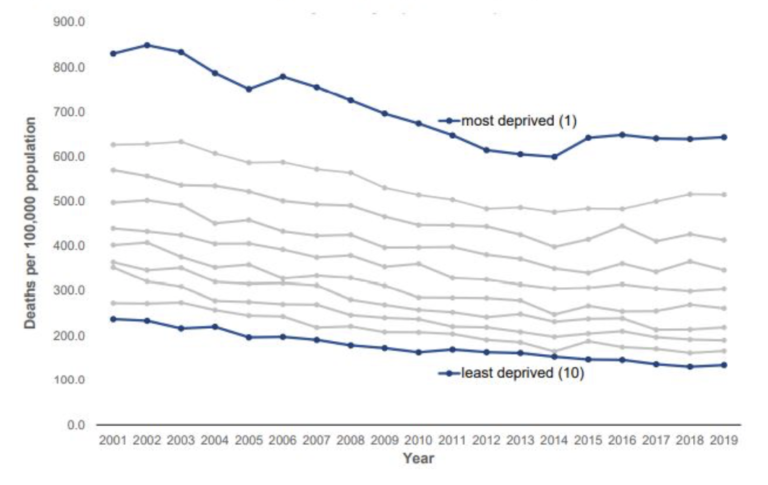

But current data shows that some key outcomes are getting worse, not better. For example, the National Records of Scotland’s most recent report shows that, after falling in every year from 2001 to 2014, avoidable mortality in Scotland has now plateaued (from 303.8 avoidable deaths per 100,000 people in 2014 307.8 in 2019). In 2019, nearly a third of all deaths – 27% – were considered avoidable. And, within Scotland, the gap between the health of the richest and the poorest is widening. The 10% most deprived Scots are nearly five times as likely to die from an avoidable death as someone in the top 10%. This is up from 3.5 times more likely compared to 2001.

Avoidable mortality rates by deprivation, all persons: 2001-2019

Back in 2005, I invited over 2000 Scots to town hall meetings to give voice to their own aspirations for their NHS and a recurrent theme was to ensure equity of access to healthcare, across any social, ethnic or other perceived divides. This is a multifaceted problem which requires joined up thinking and joined up government, transcending Ministerial departments and a frankly better performance than current evidence dictates. When the gap between the rich and the poor is widening, we must act with a greater degree of urgency.

First of all, cohesion.

We need to improve networks across healthcare in Scotland – the journey that patients take when they enter the health and social care system. In practical terms, this implies investment in patient pathways that span primary and secondary care, networks of rural hospitals linked to and supported by the major teaching hospitals, rational distribution of services between neighbouring hospitals and national planning of complex service frameworks like neurosurgery and specialised children’s services.

The technological revolution, accelerated by how we are dealing with COVID, can also support a more cohesive health service. Big data and artificial intelligence in medicine allows us to build better health profiles and better predictive models around individual patients so that we can better diagnose and treat disease and understand how individuals access the health service, to better match capacity and demand. Health care cannot be something done to us; with the help of technology, it must become a genuine partnership between health professionals and citizens. For example, the new wearables under development, track specific health trends, and relay them to the cloud where physicians can monitor them. Patients suffering from asthma or blood pressure could benefit from it, or monitors for blood oxygen levels to monitor COVID patients at home with alerts to signal when further treatment might be needed, all of which confer more independence and reduce unnecessary visits to the doctor.

The remorseless process of natural selection was summarised in October 2010 by Robert Brook of the RAND Corporation, one of the pioneers of the quality revolution 20 years ago, in a leading article in the Journal of the American Medical Association entitled ‘The end of the quality improvement movement – long live improving value’.

As we emerge from the COVID pandemic, the ensuing global economic crisis will push value further up the health agenda. In every country, ‘value’ is the key concept, and increasing value by improving outcome and reducing expenditure are the key challenges for those who deliver healthcare and those who receive it.

Secondly, collaboration.

We are never more united than when we face an existential threat such as the COVID 19 pandemic. We see high level collaboration between the four Chief Medical Officers presenting a calm, united and rational front. I am honoured to work in Oxford and have witnessed the extraordinary efforts of my colleagues who have delivered an effective vaccine and who have conducted the largest and most globally informative trials of new COVID 19 treatments. Around 29,000 patients in 176 hospital sites across the UK have been randomised to nine treatment arms, or to receive no additional treatment. During the first wave, over 10,000 patients were recruited in just two months, making it the fastest-recruiting randomised controlled trial and, in the second wave, over 6,000 patients were recruited in three weeks, demonstrating the power of unity and the necessity for collaboration across the entire UK. In my own field, medical researchers can use very large nationally collected data sets on treatment plans and recovery rates of cancer patients in order to find trends and therapies that have the highest rates of success in the real world, leading ultimately to better patient outcomes.

Finally, cooperation.

The Covid crisis has revealed just how much we require all levels of government to cooperate together when faced with a deadly, common threat. Whether it is in the supply of personal protective equipment, the roll out of a massive new testing system, or the delivery of the vaccine, we have relied on political leaders to find common cause. Together with Gordon Brown and the Our Scottish Future think-tank, we intend to make further recommendations over the coming period on how deeper cooperation across the UK can support the delivery of better healthcare for all citizens. This isn’t a constitutional dividing line – it’s about finding practical ways to get the best out of our health care system, be it in the supply of medicine, the application of technology, or the fight against a pandemic.

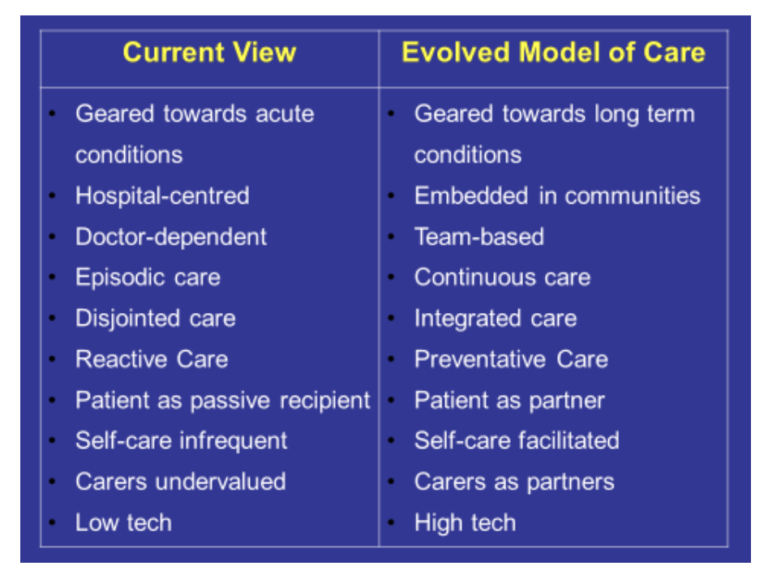

I have taken this final slide from our report of all those years ago – as true now as then, and let me ask you to judge for yourselves how far the last 15 years have taken us towards this enlightened model of how we might better deliver health to all of our folk.

Professor David Kerr is Professor of Cancer Medicine at the University of Oxford and Honorary Consultant Medical Oncologist at Oxford Cancer Centre.

Professor David Kerr was author of the National Framework for Service Change, commissioned by the then Scottish Executive in 2005 – the most wide-ranging review of how to help the NHS in Scotland manage future demand and improve health.