Aveek Bhattacharya | Twitter

Aveek Bhattacharya is Chief Economist at the Social Market Foundation, a cross-party think tank.

The new child payment will help, but more needs to be done to improve Scotland’s worryingly low birth rate.

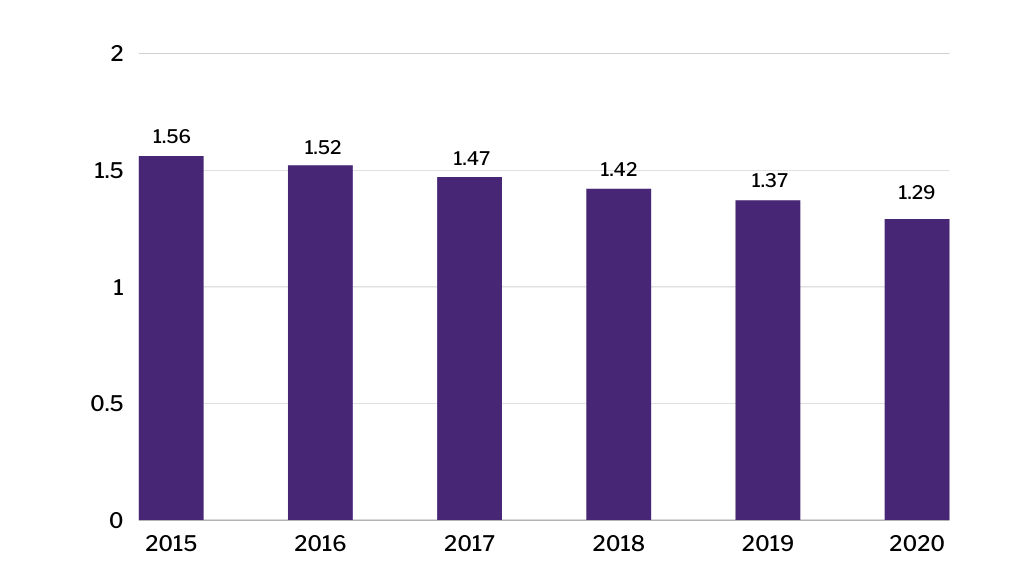

A couple of weeks ago in the Times, Robert Colvile wrote a piece worrying that Britain is ‘turning Japanese’: drifting into stagnation and economic malaise. In one important respect, Scotland is already there. The Scottish total fertility rate (TFR) – the number of children born per woman – was 1.37 in 2019. That is nearly identical to the figure for Japan – for years the go-to example of a country in demographic decline – where the TFR was 1.36 in 2019. The pandemic pushed Scottish birth rates down even further in 2020, and the TFR dropped to 1.29.

There is nothing unusual in births dropping beneath the replacement rate of 2.1 necessary to avoid long term population loss – that is the case in almost every rich country. But Scotland’s position is stark even relative to its peers. The TFR is well below England and Wales (1.58) and among the lowest in Europe. It is some distance even from 1.5 – the level below which some demographers speculate a country is at risk of getting stuck in a ‘low fertility trap’.

It isn’t immediately obvious to everybody that this is a problem, but it is. Some of the arguments here are deeply contentious. There are mind-bending philosophical wormholes we can fall into debating whether potential people are harmed by never being brought into existence. Or we could argue over the data on preferred family size and parental wellbeing and ask whether potential parents are worse-off for not having as may kids as they would like. But it is hard to avoid the conclusion that an older and smaller population is bad for us as a society.

A lower birth rate means a rising dependency ratio, with a smaller workforce to support an ever growing number of elderly people. It also weakens the economy by stifling demand: encouraging people to save rather than spend and discouraging investment from firms anticipating shrinking markets. Most fundamentally, low fertility undermines the speed of innovation: an older society risks getting increasingly stuck in its ways and a smaller population means fewer heads to work on the world’s toughest problems. That logic extends to climate change too, by the way – the loss of potential scientists and innovators will cost us more in the fight to protect the environment than any reduction in resource consumption.

The good news is that there are things governments can do to make it easier for people who want to have children to do so. The better news is that the Scottish Government has already made tentative steps in the right direction. Unfortunately, the bad news is that substantially shifting the birth rate will come at a hefty price, and it is unclear whether getting back to replacement rate is achievable.

Improving the availability and affordability of childcare, increasing the generosity of parental leave entitlements and reducing housing costs have all been shown to boost birth rates in at least some contexts. But the most direct way to support parents is through financial assistance – either tax breaks or cash payments.

As a result, the Scottish Government may have taken its first steps towards addressing its demographic challenge through the Scottish Child Payment scheme. At present, the payment provides low income families with £10 a week per child under six, but it is set to be increased to £25 and expanded to children under 16 by the end of the year. For those eligible, it will be worth a similar amount to Poland’s ‘500+’ scheme, which offers parents 500 zloty (around £100) per month for each child they have, and more valuable than the one-off French ‘birth grants’ of €950. However, unlike those other schemes, which are universal, the Scottish Child Payment is made available only to those on benefits. That targeting clearly restricts its cost and increases its effectiveness as an anti-poverty measure, but limits its impact as a policy to support birth rates. Consequently, there is more that needs to be done.

The establishment of a cross-departmental Population Taskforce, which has been in operation since 2019, is another encouraging sign that the Scottish Government is taking the problem seriously. However, it could benefit from a sharper focus on birth rates. It is striking that the total fertility rate is missing from its Population Dashboard (though the dependency ratio and number of local authorities facing population decline feature).

The task of reversing Scotland’s falling birth rate is a project lasting decades without a straightforward solution. That means that mitigating the economic pressures – by encouraging immigration and delaying retirements (not least by improving older people’s health and fitness) – is going to be important to tide us over in the short run. It is a daunting task, but one the country needs to confront head on.