A new plan is needed to turn around Scotland’s health inequalities scandal

A major new study by health academics has exposed changes in life expectancy in the USA and 19 other western nations between 2019 and 2021, the period of the pandemic.

The paper, which received widespread coverage in the US press revealed the extent of America’s increasingly dystopian social crisis. Over those two years, life expectancy fell by 2.26 years. By contrast, in the 19 other nations, the average fall was just 0.3 years. It leaves the life expectancy gap between the US and other similar nations at a shocking five years.

Within the US, it gets worse. While a white woman in the US can expect to live until she reaches the age of 80, a black man on average dies when he is just 67. Covid both exposed and widened social inequalities – and in America like no other.

America’s social ills are, of course, dominating the news this week following the awful mass shooting at a school in Texas. But before we all have our say over what is going wrong on the other side of the Atlantic, shouldn’t we look a little closer to home as well?

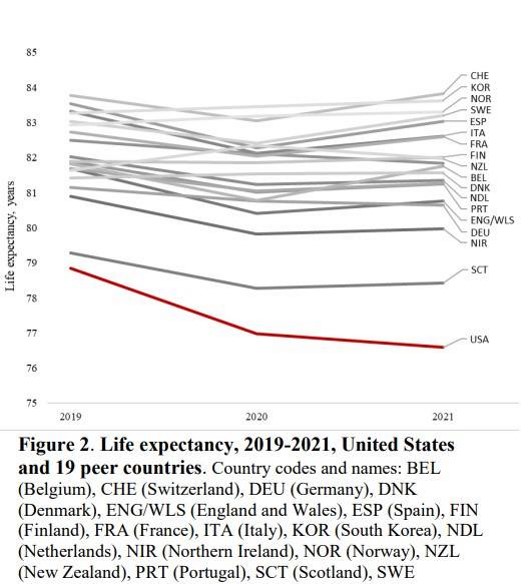

To do so, it’s worth returning to last months’ US report. Here is the graph of the 19 nations it examined.

You’ll note there are two outliers at the bottom end of the life expectancy chart. One, way down at the bottom, is the USA, where you can expect to live 76.6 years. The other is Scotland, where the figure is now 78.43. Compare that to top of the charts Switzerland where people on average live to 83.85 years of age.

According to the paper, between 2019 and 2020 – the worst Covid affected year – life expectancy in Scotland fell by a full year, well above the average of the other nations surveyed. It recovered a little between 2020 and 2021 and, in England and Wales, the drop in life expectancy was even greater. But what is notable is how all the nations of the UK fared badly compared to many others. Three countries – New Zealand, Norway, and South Korea – actually increased life expectancy between 2019 and 2021. We are doing the worst. In short, take away the USA, and Britain is bottom of the developed world’s league table, with Scotland bringing up the rear.

The figures don’t show the distribution on the income spectrum for Scotland. But we don’t really need a chart for that; existing work already tells us that men and women born in the most deprived areas have 24 fewer years in good health than those in the wealthiest. That, without a shadow of a doubt, will have widened significantly thanks to Covid.

As renowned health researcher Sir Michael Marmot summed up in a recent webinar staged by the Health Foundation think-tank: “We were doing pretty badly during Covid. And we did even worse during Covid.”

There is no consolation for anybody here. Only questions. What are the factors that lie behind Scotland’s dismal record on life expectancy? What factors influence people’s health and why is it we are faring so much worse than other nations?

Why has life expectancy begun to fall in recent years?

Fortunately, we may soon learn more about this. The Health Foundation is now carrying out a review of health inequalities in Scotland. Following a similar exercise in England, it will report back later this year. Perhaps this will help put more focus on Scotland’s current health inequalities, where it belongs.

Two contributions from the webinar seem relevant to Scotland as to how these appalling figures might be reversed.

Sir Michael was asked whether more money was the answer to this. Yes, of course, he replied. But he also added:

“It’s not just money….money is important and vital but…when I go to local government all round England and Wales and when I go to talk to people in local government I expect them to be hanging their heads in despair, wringing their hands and saying it’s all hopeless, the settlement from central government is so awful, there’s nothing we can do -, but they’re not doing that. Quite the opposite. They’re saying this is the hands, but there’s a great deal we can do despite that.”

His point was that empowered communities, in which people have a sense of agency and control, are making a difference in improving health outcomes.

The other came from Katie Kelly, the deputy chief executive of East Ayrshire Council. Since 2013, the award-winning local authority has rethought the way he it has delivered service from the “passive recipient” model to one which has pushed power into communities, putting them in control over everything from community centres, sports centres, theatre companies and golf courses.

“Investment of money in way that flips and flops only exacerbates inequalities,” she told the webinar. The way forward, she said, was “about people owning things together and having power to make change over their own lives.”

The Health Foundation’s verdict will be out in a few months’ time. Given the way the figures are heading, it can’t come a moment too soon.