Susan Dalgety | @DalgetySusan

There’s not a single politician in Scotland who does not profess to be angry or ashamed at the shocking level of our nation’s drug deaths, the worst in Europe and three-and-a-half times higher than the rest of the UK.

On the day it was revealed that a further 1,339 Scots died last year, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said it was “unacceptable” and each death was “a human tragedy.” Leader of the Scottish Tories, Douglas Ross, slammed the statistics as a “stain on Scotland,” and Scottish Labour’s Anas Sarwar insisted that the annual toll, devasting as it was, should not be the wake-up call, “the daily deaths should be.”

Sarwar is right. Every day in Scotland, three or four people die of the effects of street drug misuse. They die from a lethal cocktail of drugs, taken over years, that can include heroin, benzodiazepines (street Valium, or ‘blues’), alcohol and methadone, the legal heroin substitute prescribed to supposedly keep addicts safe. But these are not the underlying cause of their premature deaths. It is poverty and alienation that kills them.

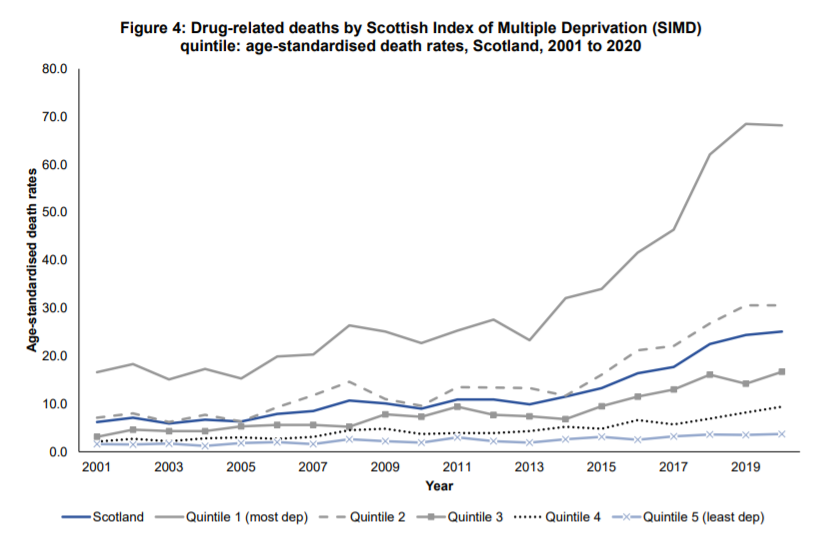

The data shows that if you live in the poorest areas of Scotland, you are 18 times more likely to die from drug misuse than your peers in more affluent neighbourhoods. Scotland’s drug epidemic mostly infects people who are already suffering from the effects of insecure employment, poor nutrition, sub-standard housing, inadequate schooling. Their addiction to the quick thrill of street drugs is their response to a life devoid of hope.

The level of drug deaths is not the only barometer of how poverty destroys lives in Scotland’s poorest communities. The latest data from the Scottish government shows that the gap in healthy life expectancy at birth between the most and least deprived areas is 25.1 years for males and 21.5 years for females. This may not have been surprising in 1921. In 2021, it is simply not acceptable.

Scotland is a very rich nation. It is part of the fifth largest economy in the world. It boasts the world’s first public education system, and was the laboratory for some of humanity’s most important inventions and discoveries, from penicillin to television. Today it is home to a global finance industry, cutting-edge life sciences, and has 19 universities attracting nearly 40 per cent of Scotland’s school leavers annually. And the Scottish government has, every year, 30 per cent more cash to spend on public services than England, thanks to the Barnett Formula.

The immediate response to Scotland’s drugs crisis is, rightly, to demand better treatment and support facilities for the 60,000 people with a drug problem, and if that means the Scottish government making different spending choices, then so be it. Free prescriptions for all, even those with healthy bank accounts, may resonate with voters at election time, but is it the best prescription for better public health? The Scottish government spent £57 million on free paracetamol alone between 2011 and 2018, yet in 2015, Scotland’s Alcohol and Drug Partnerships saw their central government funding cut by £15 million, with health boards expected to make up the difference.

Scotland has to decide what kind of country it wants to be. It is not enough to boast, as the Scottish government’s National Performance Framework does, that “We are a society which treats all our people with kindness, dignity and compassion.” We have to bring these slogans to life.

That means investing in those communities that need the most public support. The government happily subsidises the university tuition fees of middle-class school leavers while slashing frontline council services, essential to the wellbeing of children in our most deprived communities.

A teenager’s drug addiction does not start at fifteen with his first handful of ‘blues’ washed down with tooth-rotting cider. Its roots are in his mother’s poverty, his grandfather’s unemployment, his own struggle with literacy and numeracy.

Our national focus should be on supporting those children most at risk, from birth to eighteen. There are many examples of interventions that work. Labour’s Sure Start programme, which was area-based and well-resourced, is just one. Nesta, the UK innovation agency, has made this work with children its priority. “Our mission is to narrow the outcome gap between young children growing up in disadvantage and the national average,” writes Adam Lang, head of Nesta in Scotland, on its website.

And the Scottish government’s Best Start grant for babies is, well, a start. But collectively we can – must – do better. If that means, for example, a graduate tax for those privileged enough to get a degree so that national resources can be invested in children who need life-saving support, then surely that is the mark of a just nation.

It’s too late for the 1,339 Scots who died needlessly last year, but if we stop wringing our hands and start facing up to the inequality that divides our country, then we can nurture the next generation of Scots so that they all grow up safe and respected, irrespective of their family income or postcode.