Ross Newton | Twitter

Ross Newton works for Our Scottish Future

How Scottish education is failing on computing skills – and how we can turn it around

This is the most online generation in human history. Brought up on iPads rather than the streets, the online world and the real world are increasingly the same thing. Creative, savvy and entrepreneurial, this is a generation of digital natives.

You don’t have to be a policy expert to know that technology is the key to the future. It will increase efficiency, drive change and grow our economy. As we have seen in recent events, it is also paramount to our national security and resilience.

Which makes it all the more baffling that this affinity with technology is not being exploited and supported by Scotland’s education system. In fact, almost unbelievably, the exact opposite is happening.

Between 2008 and 2020 the number of computing teachers decreased from 766 to a mere 595.

It gets worse.

Over a period of 20 years the number of pupils studying computing science in Scotland has plummeted by almost 20,000 to just 9,873 pupils. There is also a growing gender divide, with girls only accounting for 1,895 of those pupils.

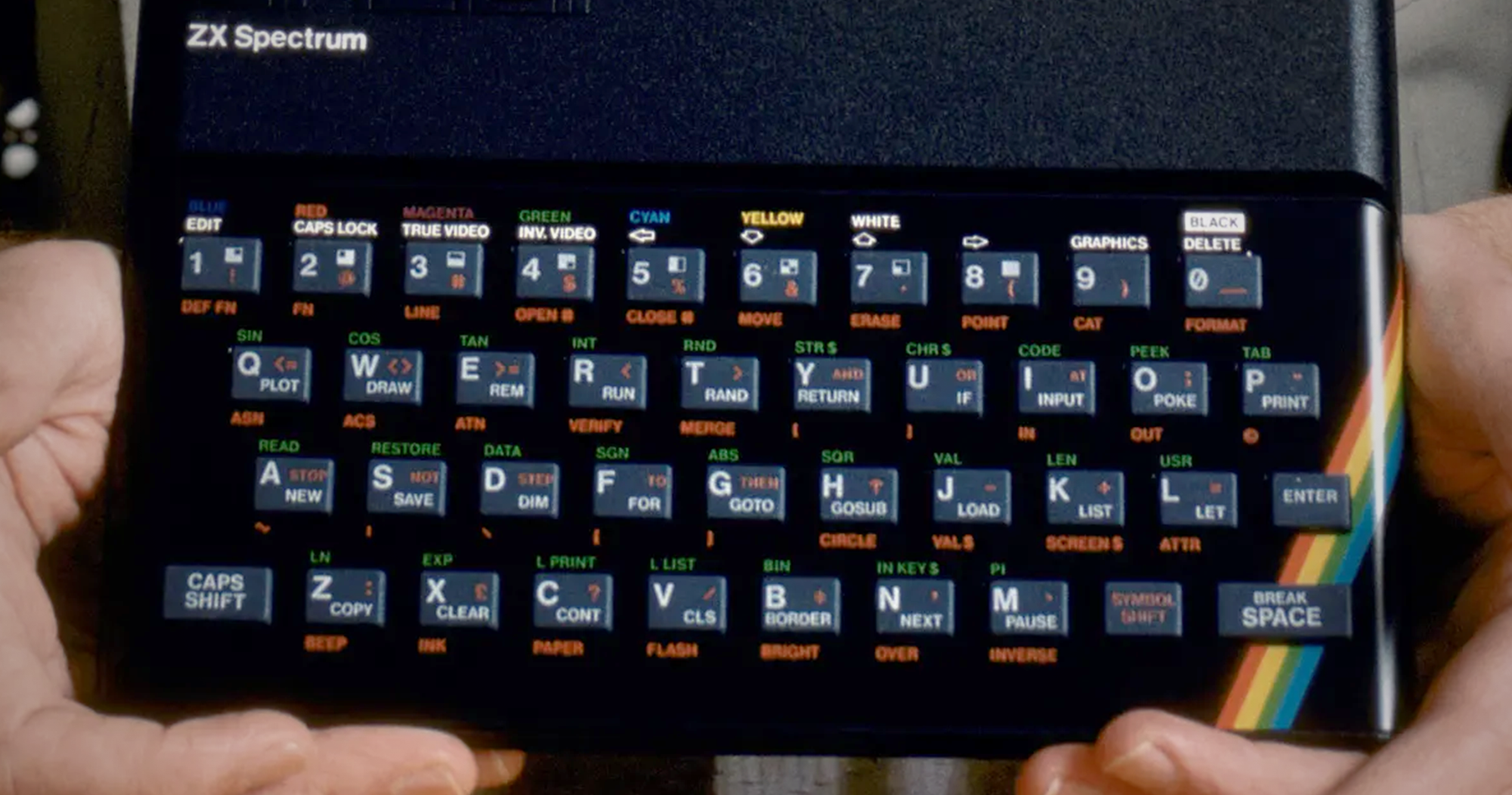

With such a fall in the number of pupils taking computing science it is worth pondering the quality of the subject. Having left school nine years ago I can only comment on my own experience of it, but it was far from thrilling. Taught by an otherwise nice elderly man (in hindsight, the entire department was male), he had clearly lost track of technological developments and often stonewalled questions. He frequently brought out his first computer (from memory I think it was the ZX Spectrum) to reminisce. Sitting in a hot classroom, the only sound the whirring of fans desperately trying to keep ageing computers from overheating as we answered (on paper) questions such as, “what is a GUI” and “list three peripheral devices” it was about as far removed from the creative dynamic buzz of Silicon Valley as you can get.

As has sadly become clear, the Scottish government are very good at talking the language of the future yet their actions frequently betray them. That such a widely recognised field of economic and national importance has been allowed to atrophy in our schools is nothing short of scandalous.

It reeks of shortsightedness and strategic incoherence. Earlier this year the Scottish government announced a “boost” of £1.3m for computing in schools allowing them to bid for grants up to £3,000. This is to allow schools to purchase equipment and more general resources. Some money is always better than no money, but for context, I’m typing this on a laptop that cost over £1,200 and is hardly top of the range. The Scottish government’s flagship policy to give school children a free “computer device” is also lagging far behind with it being reported that fewer than one in five schoolchildren have received one.

Thankfully, Scotland’s world class universities have excelled in developing technological expertise, yet even this will now come under threat with the cuts to education being recently announced by Kate Forbes. This at a time when universities should be central to our economy is economic illiteracy and comes as research from ScotlandIS suggests that 75% of employers are struggling to recruit staff suitably qualified in digital.

As a small nation we need to decide upon an economic strategy and invest in it. We need to look to areas we have strength in and, to steal from the new German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, “re-industrialise” in the industries of the future. Scotland already boasts a world class gaming industry. A recent paper by Our Scottish Future identified this is a national asset in an industry with high growth potential. The Scottish government should be developing a strategy that allows this to flourish, not stifling potential in schools with a lack of support, investment and courses that still reference floppy disks. The gender divide in pupils taking computing as a subject must also be tackled to increase the talent pool.

We see the potential in young people every day. The governments job is to support it. Across the world governments are recognising that computing and its offshoots are vital to success and making it a priority. Scotland’s children deserve the same opportunity.