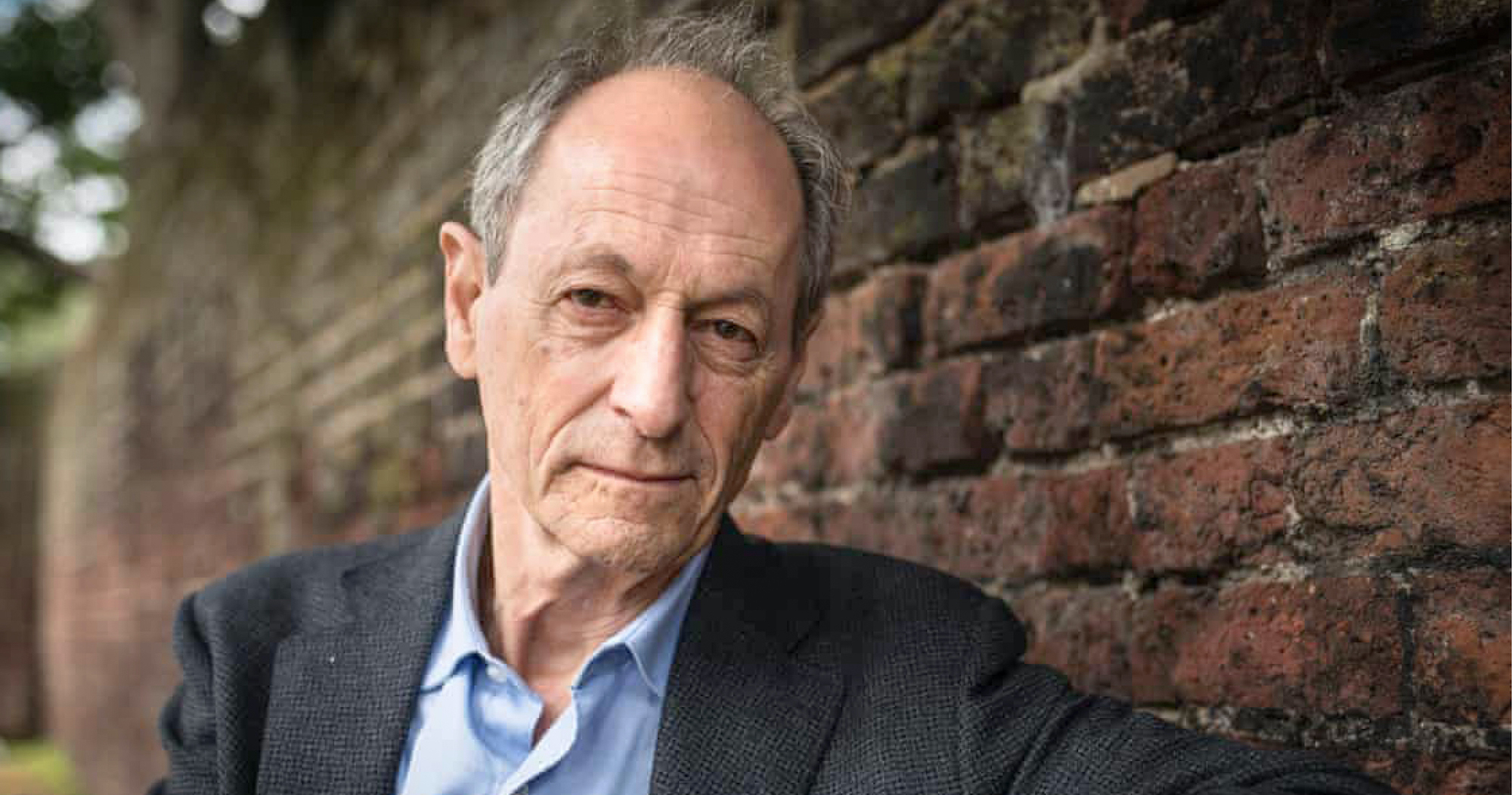

Prefer video? You can watch an extract of the interview with Sir Michael Marmot, on which this article was based, here.

If you want to study the devastating impact the Covid pandemic has had on society, Sir Michael Marmot suggests we go back to 2017 and a storm in the Caribbean.

Back then, Hurricane Maria smashed through the tiny island of Puerto Rico in one of the deadliest storms ever to hit the island. Two months afterwards, with the island’s infrastructure battered, records showed that the number of deaths had risen markedly – but not uniformly. While the wind had blown with equal ferocity across the island, few wealthy residents had been touched. Among the island’s poorest people, however, excess deaths shot up sharply. The Hurricane thrust the underlying inequalities in Puerto Rican society into sharp relief.

The Puerto Rico analogy formed part of a new report by Sir Michael on how the Covid pandemic hit our own society. One of the world’s foremost experts on health inequality, Marmot has spent a career showing how the quality of peoples’ health is intimately related to what he describes as our “social determinants” – our income, our quality of life, our housing, environment, and education. The report “Build Back Fairer” concluded that just as the hurricane exposed the social factors behind your chances of survival in the Caribbean, so the pandemic has revealed the same in the UK. His studies show that people living in over-crowded housing – where social distancing is harder – were among the most likely to die. They reveal that the death rates of under 65s were highest among carers and people working in leisure and service industries – again, because they were more exposed. People from ethnic minority groups – who are more likely to work as taxi drivers, security guards, or in factories – had a much higher risk of death than the white population. The wealthier you are, the safer you were.

“What we have seen over the year of the pandemic is a revealing – an amplification – of the underlying inequalities,” he says. It is not just risk of death, the pandemic has widened economic inequalities more generally.

“In general the lower your income, the greater the likelihood that you would be employed in a sector that was shut down,” he notes. “So if you were on a furlough scheme you’d get 80% of your income which makes you a bit poorer or not get income or furlough at all. But if you were on a higher income, you were not employed in a shuttered sector so your income was maintained, Not only that you couldn’t go to the Opera, or fly to the Caribbean for a holiday, so what are you going to do with that money? Well, get richer, that’s what you’re going to do”

The pandemic has been, for many of us, a break point. Many are asking if there is a better way forward for the UK and Scotland than the way we were run before. We are catching up with where Sir Michael has been for some time. Twelve months ago, in February last year – before the pandemic – he wrote a major report urging just such a shift. Focussing his research on England, the paper found that people could now expect to spend more of their lives in poor health, that the health gap between wealthy and deprived areas had widened and the improvements to life expectancy had stalled. This was itself ten years on from the ground-breaking Marmot Review, examining health inequalities in England, arguing the same. “The worst thing would be to re-establish the status quo and go back to where we were in February 2020. That report said that where we have been over the last ten years is not a good place,” he says.

“I wasn’t arguing it on political grounds, it was on health grounds. Health had stopped improving and inequalities had got bigger and health for the poorest people was getting worse. I argued it on those grounds.”

“I’d like to think if you read my report you’d say that whatever was happening (between 2010 and 2020) wasn’t good. If you accept my overall conclusion that the nature of society has a fundamental impact on health and inequalities then you’d say society wasn’t going very well those last ten years.”

In short, the cuts and inequality of post-crash Britain had caused people to die younger, and for inequalities to widen. With the pandemic having made things worse, the question Marmot poses is how we now bring society back fairer. This is, of course, partly about income, and he supports short-term measures such as a reversal of benefit cuts and more generous furlough schemes. But it is more than that – it is about creating what he describes as a “life of dignity” for people across society.

This was something, he notes, that we once perhaps had in Britain but, in the modern era, of service jobs and globalised finance, is lacking. “If you were working in the shipyards in Strathclyde – and I don’t want to be too romantic – you had a good job, a job for life, a good career, that co-workers felt was meaningful. Then you close the shipyards and all that is gone.”

“I’ve been reading (Poverty Safari author) Darren McGarvey and (the Booker prizewinning novel) Shuggie Bain…. a life of dignity doesn’t just come from nowhere, it comes from the conditions in which you are born, grow, live and age and from the inequities in power, money and resources. Yes, money is part of it, but only one part of it.”

If we are to bring back society better and fairer, then he argues we require a deep shift in our thinking – one which takes the accumulation of GDP as a nation’s national prime measure of success and replaces it with the general health and wellbeing of its people. Why bother with GDP, he argues, if – as happened over the last decade – health stopped improving and health inequalities got bigger?

So, as people ask how to “build back fairer”, here are Marmot’s thoughts.

“I would start with pre-school. Education is vital but what happens to children before they get into school is more important”. Over the last decade, closures to Sure Start Centres in England – which made pre-school education harder – and the rise in relative child poverty, both had adverse impacts on early child development, he argues. He is fiercely critical of the reduction in per pupil spending in England over the decade. “Which politician thought: ‘I’ve got a good idea, let’s reduce spending on education?’….I don’t know what goes through people’s heads.”

And he would then put equity of health and well-being at the heart of government policy. Turning to Scotland, he notes that good intentions require action. “When Harry Burns was Chief Medical Officer in Scotland, he would say ‘I think we are more like a Nordic country than we are an Anglo Saxon country’. I would say that’s a laudable ambition, and I would ask but is it true in fact? I would like to look at that. Scotland has worse health than England in general so we know the challenges are big in Scotland.”

He adds: “Across the whole system in Scotland you have a minister for early childhood who comes under Education, and then sport, and then communities and you have got ministers that deal with all of this. What they do is vital for health and health equity. …Put equity of health and wellbeing at the heart of all government policy.”

And focus, he says, on six “domains”: “early childhood, education, employment and working conditions, having enough money to live on, health and sustainable places to live and work, and taking a social determinants approach to prevention . Dealing with the social and economic context in which people drink and smoke and do exercise.”

“What we don’t need is the Secretary of State for Education saying ‘yes, I’m very worried about health, I’ll make sure the children run around the park once a week’. Running around the park is very good for children and if they could do it every day that would be even better but that’s not what I mean. I’m not against it – what I mean is that we want all children to finish their voyage through education system with two kinds of things.”

“One is the basics, what you learn, reading, writing the basics, so you can pass exams and get jobs and fill in forms. But the second is the life skills that education ideally teaches you – how to deal with figures of authority, how to deal with your peers, the social emotional behavioural skills , the cognitive abilities that you need to function in a complex society.”

Marmot recalls how he once advised a government finance minister in Brazil to make health and health inequalities the “social accountant” for how well their society was faring. The minister replied that every day he had 18 different people making their case: housing, jobs, football, and so on. Marmot replied that it was health that tied them all together.

“I do think health is the outcome of all the other things. If you’re Brazilian maybe football is the outcome but even if you’re Brazilian then you’d recognise that everyone thinks health is the big thing.”

“Health and health inequalities should be a kind of social accountant. They’re the measure of how well we are doing with all the rest.”